Chapter 2 Building verbal models of the matching pennies game

2.1 Trying out the game and collecting your own data

Today’s practical exercise is structured as follows:

In order to do computational models we need a phenomenon to study (and ideally some data), you will therefore undergo an experiment, which will provide you with two specific cognitive domains to describe (one for now, one for later), and data from yourselves.

You will now have to play the Matching Pennies Game against each other. In the Matching Pennies Game you and your opponent have to choose either “left” or “right” to indicate the hand in which the penny is hidden. If you are the matcher, you win by choosing the same as your opponent. If you are the hider with the penny, you win by choosing the opposite as your opponent.

You should run 30 rounds with one of you being the hider and the other the matcher and then exchange roles for 30 more rounds. When you are the matcher, keep track of your score: every time you guess right you get +1, every time you don’t you get -1. The hider gets exactly the opposite, so if the matcher ends with a negative score, the hider has won and vice versa.

Given you play many trials the game can take a while. If you want to take a break or do it in two sessions, feel free!

Try to pay attention and aim at winning. As you play also try to figure out what kind of strategies might be at play for you and for the opponents. How are you deciding whether to choose left or right? Feel free to take notes.

2.2 Start Theorizing

The goal of today’s assignment is to build models of the strategies and cognitive processes underlying behavior in the matching pennies game. In other words, to build hypotheses as to how the data is generated. The goal is to: 1) get you more aware of the issue of theory building (and assessment); 2) identify a small set of verbal models that we can then formalize in mathematical cognitive models and algorithms for simulations and model fitting.

First, let’s take a little free discussion:

Did you enjoy the game?

What was the game about?

What do you think your opponent was doing?

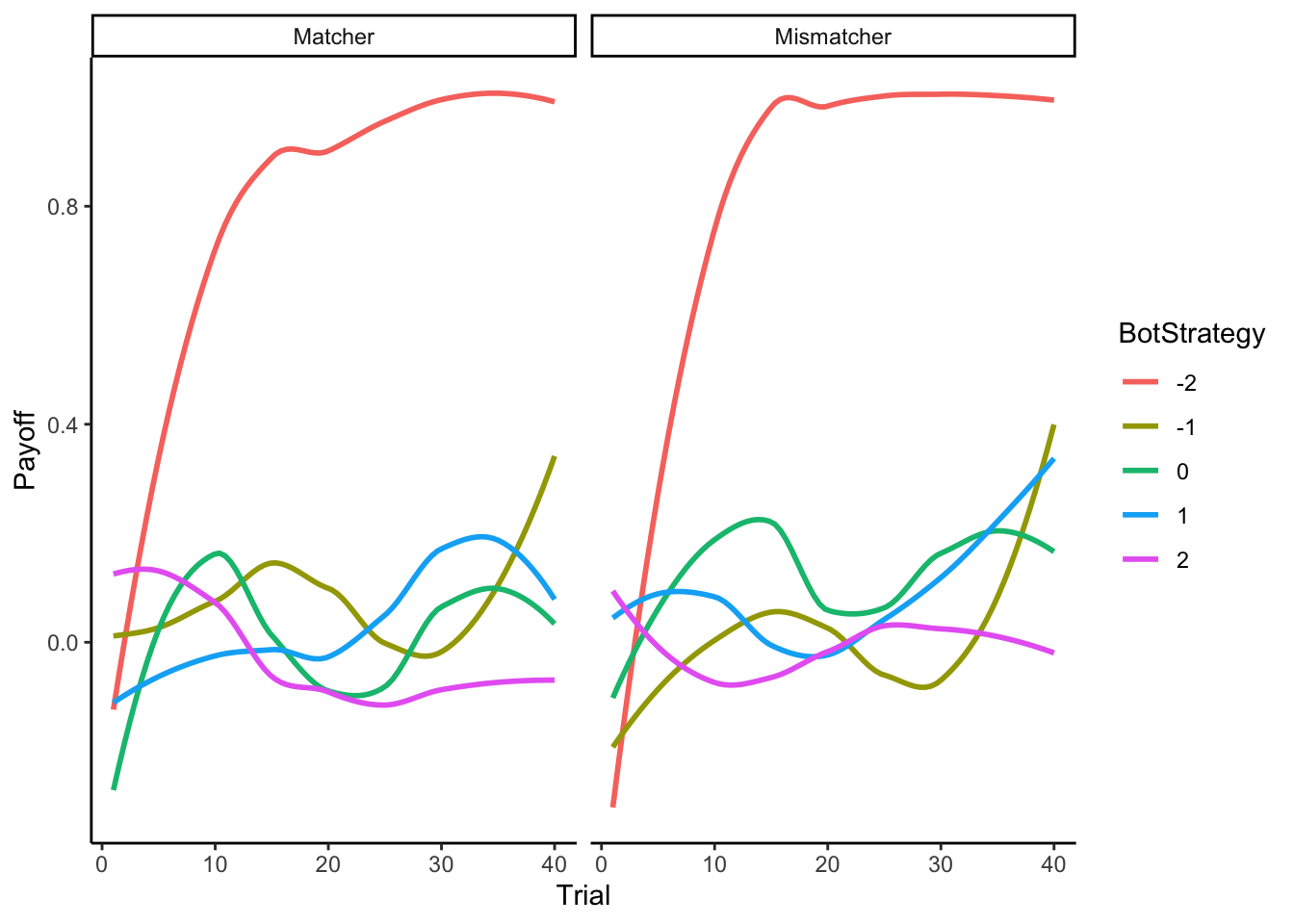

Below you can observe how a previous year of CogSci did against bots (computational agents) playing according to different strategies. Look at the plots below, where the x axes indicate trial, the y axes how many points the CogSci’ers scored (0 being chance, negative means being completely owned by the bots, positive owning the bot) and the different colors indicate different strategies employed by the bots. Strategy “-2” was a Win-Stay-Lose-Shift bot: when it got a +1, it repeated its previous move (e.g. right if it had just played right), otherwise it would perform the opposite move (e.g. left if it had just played right). Strategy “-1” was a biased Nash both, playing “right” 80% of the time. Strategy “0” indicates a reinforcement learning bot; “1” a bot assuming you were playing according to a reinforcement learning strategy and trying to infer your learning and temperature parameters; “2” a bot assuming you were following strategy “1” and trying to accordingly infer your parameters.

library(tidyverse)

d <- read_csv("data/MP_MSc_CogSci22.csv") %>%

mutate(BotStrategy = as.factor(BotStrategy))

d$Role <- ifelse(d$Role == 0, "Matcher", "Hider")

ggplot(d, aes(Trial, Payoff, group = BotStrategy, color = BotStrategy)) +

geom_smooth(se = F) +

theme_classic() +

facet_wrap(.~Role)

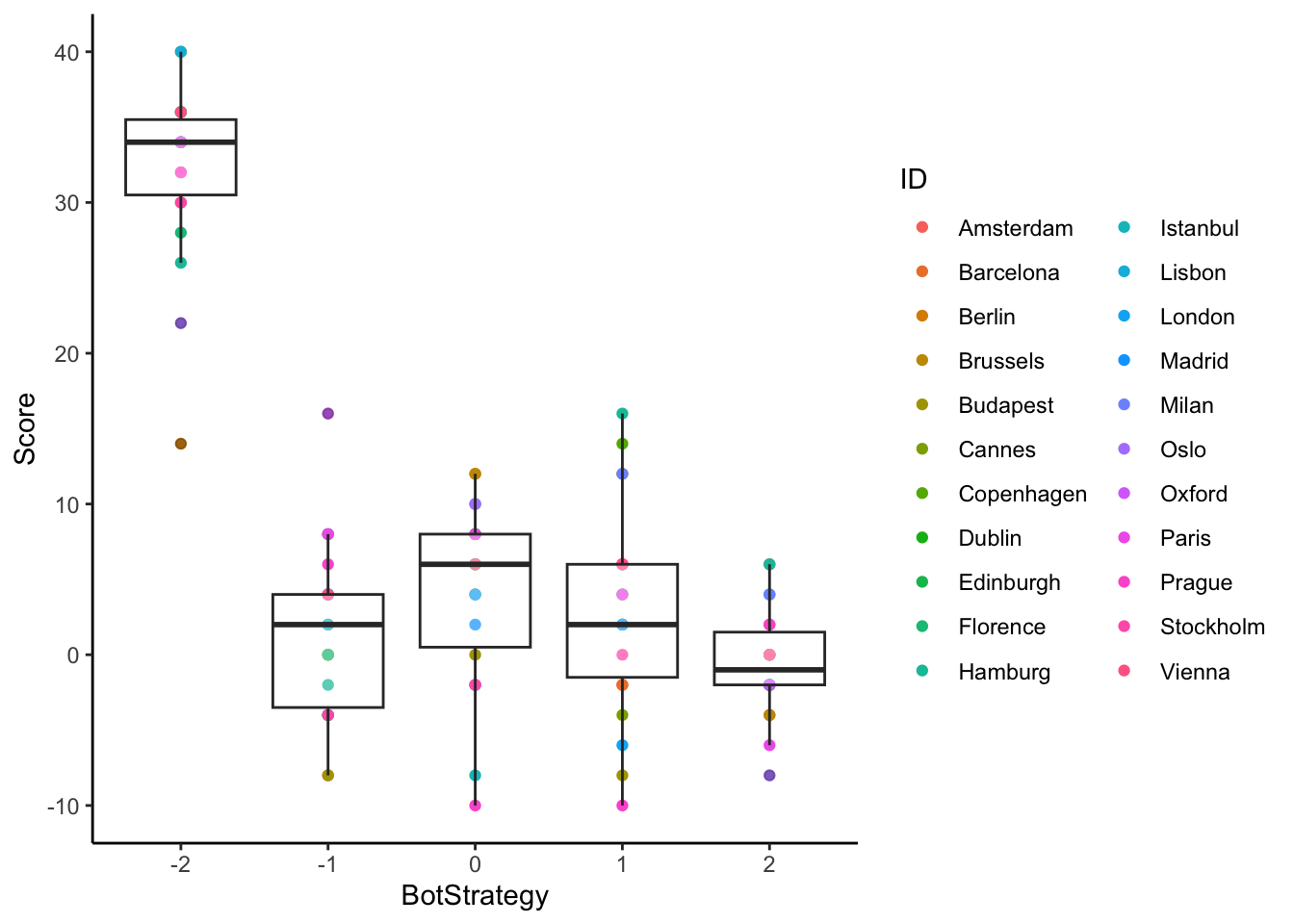

That doesn’t look too good, ah? What about individual variability? In the plot below we indicate the score of each of the former students, against the different bots.

d1 <- d %>% group_by(ID, BotStrategy) %>%

dplyr::summarize(Score = sum(Payoff))

ggplot(d1, aes(BotStrategy, Score, label = ID)) +

geom_point(aes(color = ID)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha = 0.3) +

theme_classic()

Now, let’s take a bit of group discussion. Get together in groups, and discuss which strategies and cognitive processes might underlie your and the agents’ behaviors in the game. One thing to keep in mind is what a model is: a simplification that can help us make sense of the world. In other words, any behavior is incredibly complex and involves many complex cognitive mechanisms. So start simple, and if you think it’s too simple, progressively add simple components.

Once your study group has discussed a few (during the PE), let’s discuss them. Here are the key points from the previous runs of the activity.

2.3 The distinction between participant and researcher perspectives

As participants we might not be aware of the strategy we use, or we might believe something erroneous. The exercise here is to act as researchers: what are the principles underlying the participants’ behaviors, no matter what the participants know or believe? Note that talking to participants and being participants helps developing ideas, but it’s not the end point of the process. Also note that as cognitive scientists we can rely on what we have learned about cognitive processes (e.g. memory).

Another important component of the distinction is that participants leave in a rich world: they rely on facial expressions and bodily posture, the switch strategies, etc. On the other hand, the researcher is trying to identify one or few at most “simple” strategies. Rich bodily interactions and mixtures or sequences of multiple strategies are not a good place to start modeling. These aspects are a poor starting point for building your first model, and are often pretty difficult to fit to empirical data. Nevertheless, they are important intuitions that the researcher should (eventually?) accommodate.

2.4 Strategies

2.4.1 Random strategies

Players might simply be randomly choosing “head” or “tail” independently on the opponent’s choices and of how well they are doing. Choices could be fully at random (50% “head”, 50% “tail”) or biased (e.g. 60% “head”, 40% tail).

2.4.2 Immediate reaction

Another simple strategy is simply to follow the previous choice: if it was successful keep it, if not change it. This strategy is also called Win-Stay-Lose-Shift (WSLS).

Alternatively, one could do the opposite: Win-Shift-Lose-Stay.

2.4.3 Keep track of the bias (perfect memory)

A player could keep track of biases in the opponent: count the proportion of “head” on the total trials so far and choose whichever choice has been made most often by the opponent.

2.4.4 Keep track of the bias (imperfect memory)

A player could not be able to keep in mind all previous trials, or decide to forget old trials, in case the biase shifts over time. So we could use only the last n trials, or do a weighted mean with weigths proportional to temporal closeness (the more recent, the higher the weight).

2.4.5 Reinforcement learning

Since there is a lot of leeway in how much memory we should keep of previous trials, we could also use a model that explicitly estimates how much players are learning on a trial by trial basis (high learning, low memory; low learning, high memory). This is the model of reinforcement learning, which we will deal with in future chapters. Shortly described, reinforcement learning assumes that each choice has a possible reward (probability of winning) and at every trial given the feedback received updates the expected value of the choice taken. The update depends on the prediction error (difference between expected and actual reward) and the learning rate.

2.4.6 k-ToM

Reinforcement learning is a neat model, but can be problematic when playing against other agents: what the game is really about is not assessing the probability of the opponent choosing “head” generalizing from their past choices, but predicting what they will do. This requires making an explicit model of how the opponent chooses. k-ToM models will be dealt with in future chapters, but can be here anticipated as models assuming that the opponent follows a random bias (0-ToM), or models us as following a random bias (1-ToM), or models us modeling them as following a random bias (2-ToM), etc.

2.4.7 Other possible strategies

Many additional strategies can be generated by combining former strategies. Generating random output is hard, so if we want to confuse the opponent, we could act first choosing tail 8 times, and then switching to a WSLS strategy for 4 trials, and then choosing head 4 times. Or implementing any of the previous strategies and doing the opposite “to mess with the opponent”.

2.5 Cognitive constraints

As we discuss strategies, we can also identify several cognitive constraints that we know from former studies: in particular, memory, perseveration, and errors.

2.5.1 Memory

Humans have limited memory and a tendency to forget that is roughly exponential. Models assuming perfect memory for longer stretches of trials are unrealistic. We could for instance use the exponential decay of memory to create weights following the same curve in the “keeping track of bias” models. Roughly, this is what reinforcement learning is doing via the learning rate parameter.

2.5.2 Perseveration

Winning choice is not changed. People tend to have a tendency to perseverate with “good” choices independently of which other strategy they might be using.

2.5.3 Errors

Humans make mistakes, get distracted, push the wrong button, forget to check whether they won or lost before. So a realistic model of what happens in these games should contain a certain chance of making a mistake. E.g. a 10% chance that any choice will be perfectly random instead of following the strategy.

Such random deviations from the strategy might also be conceptualized as explorations: keeping the door open to the strategy not being optimal and therefore testing other choices. For instance, one could have an imperfect WSLS where the probability of staying if winning (or shifting if losing) is only 80% and not 100%. Further, these deviations could be asymmetric, with the probability of staying if winning is 80% and of shifting if losing is 100%; for instance if negative and positive feedback are perceived asymmetrically.

2.6 Continuity between models

Many of these models are simply extreme cases of others. For instance, WSLS is a reinforcement learning model with an extreme learning rate (reward replaces the formerly expected value without any moderation), which is also a memory model with a memory of 1 previous trial. k-ToM builds on reinforcement learning: at level 1 assumes the other is a RL agent.

2.7 Mixture of strategies

We discussed that there are techniques to consider the data generated by a mixture of models: estimating the probability that they are generated by model 1 or 2 or n. This probability can then be conditioned, according to our research question, to group (are people w schizophrenia more likely to employ model 1) or ID (are different participants using different models), or condition, or… We discussed that we often need lots of data to disambiguate between models, so conditioning e.g. on trial would in practice almost (?) never work.

2.8 Differences from more traditional (general linear model-based) approaches

In a more traditional approach we would carefully set up the experiment to discriminate between hypotheses. For instance, if the hypothesis is that humans deploy ToM only when playing against intentional agents, we can set agents with increasing levels of k-ToM against humans, set up two framings (this is a human playing hide and seek, this is a slot machine), and assess whether humans perform differently. E.g. whether they perform better when thinking it’s a human. We analyze performance e.g. as binary outcome on a trial by trial base and condition its rate on framing and complexity. If framing makes a difference in the expected direction, we are good.

If we do this properly, thanks to the clever experimental designs we set up, we can discriminate between hypotheses. And that is good. However, cognitive modeling opens additional opportunities. For instance, we can actually reconstruct which level of recursion the participants are enacting and if it changes over time. This might be very useful in the experimental setup, and crucial in more observational setups. Cognitive modeling also allows us to discriminate between different cognitive components more difficult to assess by looking at performance only. For instance, why are participants performing less optimally when facing a supposedly non-intentional agent? Is their learning rate different? Is their estimate of volatility different?

In other setups, e.g. a gambling context, we might observe that some participants (e.g. parkinson’s patients) are gambling away much. Is this due to changes in their risk-seeking propensities, loss aversion, or changes in the ability to actually learn the reward structure? Experimental setups help, but cognitive modeling can provide more nuanced and direct evidence.